Word classes

1. Problem and history

Does the frequency of different word classes abide by a special distribution law? Evidently, word classes are nominal entities, thus they must be ranked (see Ranking →). Historically, word classes represent the diversification of an amorphous word stock which began to be partitioned by the development of grammar, thus this is a problem of diversification (→).

The first investigations have been performed by Hammerl (1990) who obtained the Zipf-Alekseev distribution, just as Schweers, Zhu (1991) did. Köhler (1991) studied the problem from the diversification point of view. A number of individual studies on texts in German (Best 1994, 1997, 2000, 2001a, b; Judt 1995), Russian (Bosselmann 2001), French (Judt 1995), Latin (Schweers, Zhu 1991) Chinese (Zhu, Best 1992, Schweers, Zhu 1991), Czech (Uhlířová 2000) and Portuguese (Ziegler 1998, 2001) has been performed and brought different results. The word classes were considered in their classical version, nobody tested other possible classifications. Statistical tests for word classes have been set up by Wimmer and Altmann (2001). The hypothesis concerning word classes is merely a special case of a more general hypothesis encompassing any kind of classes of linguistic entities.

2. Hypothesis

If language entities are ordered in classes, then their ranked frequencies follow a regular probability distribution or a regular ranking series.

Seen from the opposite point of view, if the ranked frequencies are properly distributed we have a preliminary approximate corroboration of the “correctness” of the classification, i.e. we approximate some linguistic-psychological truth.

3. Derivation

3.1. The Zipf-Alekseev distribution

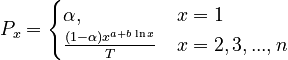

The derivation is shown in Word associations ( ), Chapter 3.1. Different derivations are shown in Hammerl (1990) and Hřebíček (2000: 14f). The formula used in right truncated form and with modified class

), Chapter 3.1. Different derivations are shown in Hammerl (1990) and Hřebíček (2000: 14f). The formula used in right truncated form and with modified class  is

is

,

,

where  .

.

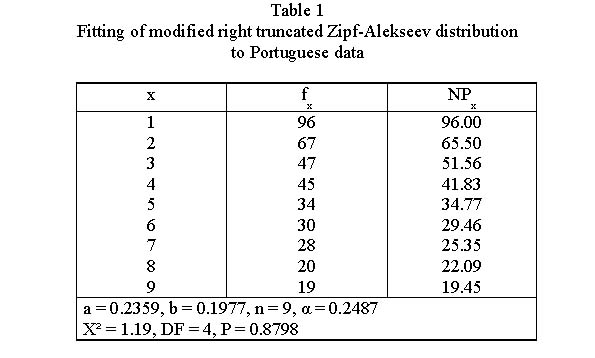

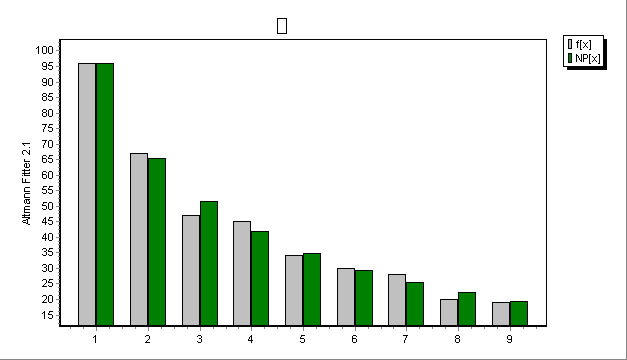

Example: Word classes in Portuguese (Ziegler 2001).

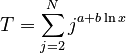

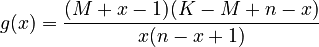

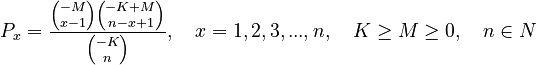

3.2. The negative hypergeometric distribution

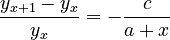

The frequency of ranked word classes abides by the usual proportionality relation between neighboring classes. Using the proportionality function

and solving with displacement

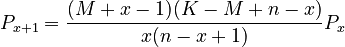

(1)

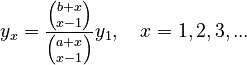

one obtains the 1-displaced negative hypergeometric distribution

(2)

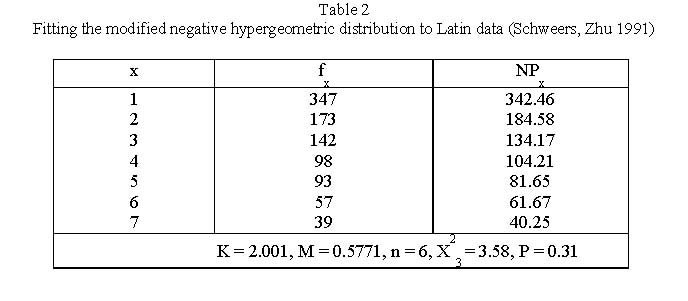

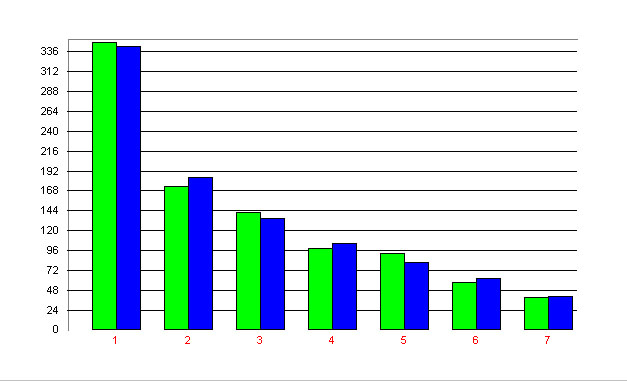

Example: Word classes in Latin (Schweers, Zhu 1991) Schweers and Zhu examined word classes in Latin, German and Chinese and found satisfactory fits for Latin and German. For Latin, they took Caesar´s “Bellum Gallicum”, Book 1, Chapters 1-8, § 2, and obtained the results in Table 2. The majority of researchers used this distribution.

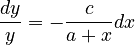

3.3. Altmann´s series

Altmann (1993) did not strive for a distribution but simply for a series capturing the decreasing frequencies (absolute or relative) of ranked classes. Consider the Zipf-Mandelbrot law as a (not normalized) continuous function. Its differential equation is

(2)  ,

,

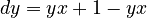

i.e. a special case of the unified theory (→). Since ranking proceeds in unit steps,  and

and  , we obtain

, we obtain

(3)  .

.

Reordering, setting  , and solving (3), results in

, and solving (3), results in

(4)

The parameters fulfill one of the conditions (i)  , (ii)

, (ii)  ,

,  , (iii)

, (iii)  when

when  and

and  are not integers.

are not integers.

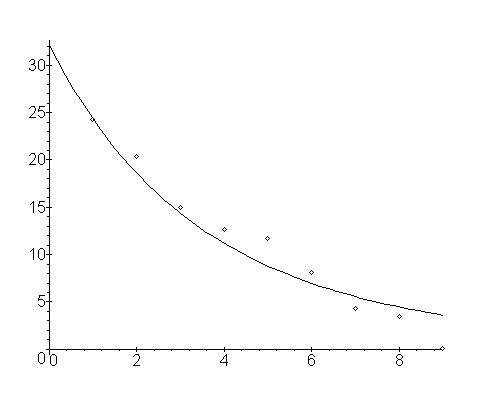

Example: Word class distribution in a German text (Best 1997)

Altmann used (4) only for phoneme ranking, but Best (1994, 1997) used it also for word classes with very satisfactory results. The fitting of (4) to the relative frequencies of word classes in a German text (Bichsel, P., Der Mann, der nichts mehr wissen wollte) yielded results presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

Here  are the ranked word classes,

are the ranked word classes,  are their relative frequencies. The fit is very satisfactory.

are their relative frequencies. The fit is very satisfactory.

4. Authors: U. Strauss, G. Altmann, K.-H. Best

5. References

Altmann, G. (1991). Word class diversification of Arabic verbal roots. In: Rothe, U. (ed.), Diversification Processes in Language: Grammar: 57-59. Hagen: Rottmann.

Altmann, G. (1993). Phoneme counts. Glottometrika 14, 55-70.

Best, K.-H. (1994). Word class frequencies in contemporary German short prose texts. J. of Quantitative Linguistics 1, 144-147.

Best, K.-H. (1997). Zur Wortartenhäufigkeit in Texten deutscher Kurzprosa der Gegenwart. Glottometrika 16, 276-285.

Best, K-H. (1998). Zur Interaktion der Wortarten in Texten. Papiere zur Linguistik 58: 83-95.

Best, K.-H. (2000). Verteilung der Wortarten in Anzeigen. Göttinger Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 4, 37-51.

Best, K.-H. (2001a). Zur Gesetzmäßigkeit der Wortartenverteilungen in deutschen Pressetexten. Glottometrics 1, 1-26.

Best, K.H. (2001b). Quantitative Linguistik. Eine Annäherung. Göttingen: Peust & Gutschmidt.

Bosselmann, A. (2001). Wortartenverteilungen in russischen Texten. Msc.

Hammerl, R. (1990). Untersuchungen zur Verteilung der Wortarten im Text. Glottometrika 11, 142-156.

Hřebíček, L. (2000). Variation in sequences. Prague: Oriental Institute.

Hudson, R. (1994). About 37 % of word-tokens are nouns. Language 70, 331-339.

Judt, B. (1995). Wortartenhäufigkeiten im Deutschen und Französischen. Göttingen: Staatsexamensarbeit.

Köhler, R. (1991). Diversification of coding methods in grammar. In: Rothe, U. (ed.), Diversification Processes in Language: Grammar: 47-55. Hagen: Rottmann.

Lauter, J. (1966). Untersuchungen zur Sprache von Kants “Kritik der reinen Vernunft”. Köln: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Mizutani, S. (1989). Ohno's lexical law: its data adjustment by linear regression. In: Mizutani, S. (ed.), Japanese Quantitative Linguistics. Bochum: Brockmeyer. 1-13.

Schindelin, C. (2005). Die quantitative Erforschung der chinesischen Sprache und Schrift. In: Köhler, R., Altmann, G., Piotrowski, R.G. (eds.), Quantitative Linguistics - An Inernational handbook: 947-970. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Schweers, A., Zhu, J. (1991). Wortartenklassifikation im Lateinischen, Deutschen und Chinesischen. In: Rothe, U. (ed.), Diversification Processes in Language: Grammar: 157-167. Hagen: Rottmann.

Uhlířová, L. (2000). On language modelling in automatic speech recognition. J. of Quantitative Linguistics 7, 209-216.

Wimmer, G., Altmann, G. (2001). Some statistical investigations concerning word classes. Glottometrics 1, 109-123.

Zhu, J, Best, K.-H. (1992). Zum Wort im modernen Chinesisch. Oriens Extremus 35, 45-60.

Ziegler, A. (1998). Word class frequencies in Brazilian-Portuguese texts. J. of Quantitative Linguistics 5, 269-280.

Ziegler, A. (2001). Word class frequencies in Portuguese press texts. In: Uhlířová, L., Wimmer, G., Altmann, G., Köhler, R. (eds.), Text as a Linguistic Paradigm: Levels, Constituents, Constructs. Festschrift in Honour of Ludek Hřebíček: 295-312. Trier: WVT.

Ziegler, A., Best, K.-H., Altmann, G. (2002). Nominalstil. ETC 2, 72-85.

Ziegler, A., Best, K.-H., Altmann, G. (2001). A contribution to text spectra. Glottometrics 1, 97-108.